Subdividing the Sphere: How I Arrived at the Same Architecture as Uber’s H3

About 9 years ago I was working as a backend engineer at a small ride-hailing startup while finishing my CS degree. I decided to connect my diploma project with my day job — the most interesting task we had was demand prediction. We had real data to train on, and it looked promising. So I started.

What is “this area”?

The task: given a GPS coordinate and a time, predict how many ride requests will come from this area. The immediate question — what exactly is “this area”?

A circle of fixed radius? That’s continuous and high-dimensional — hard to train on. You need to discretize the map into zones. We also wanted to visualize the demand map for drivers, so having well-defined, visually clean zones mattered.

I knew about geo-indexes like geohash, but they didn’t feel right. The most trivial option — squares, like a chessboard over the map.

Why not squares?

Hexagons turned out to be a much better fit. Every hex has 6 neighbors, all equidistant from the center — no diagonal ambiguity like squares have. They approximate circles better than any other tessellating polygon, which matters when you’re thinking about a driver’s reachable area. The Red Blob Games post lays out the case thoroughly if you’re curious.

I was convinced. Hexagons it is.

The sphere problem

One catch: it’s mathematically impossible to tile a sphere with only hexagons. Euler’s polyhedron formula guarantees you’ll always need exactly 12 pentagons. This is the core challenge of any global hexagonal grid system.

My solution: recursive triangle subdivision

Instead of tiling the sphere with hexagons directly, I started with an octahedron — 8 spherical triangles covering the entire Earth, formed by splitting the globe along the equator and the prime/180° meridians:

NE1, NE2 (northern-eastern quadrants)

NW1, NW2 (northern-western quadrants)

SE1, SE2 (southern-eastern quadrants)

SW1, SW2 (southern-western quadrants)

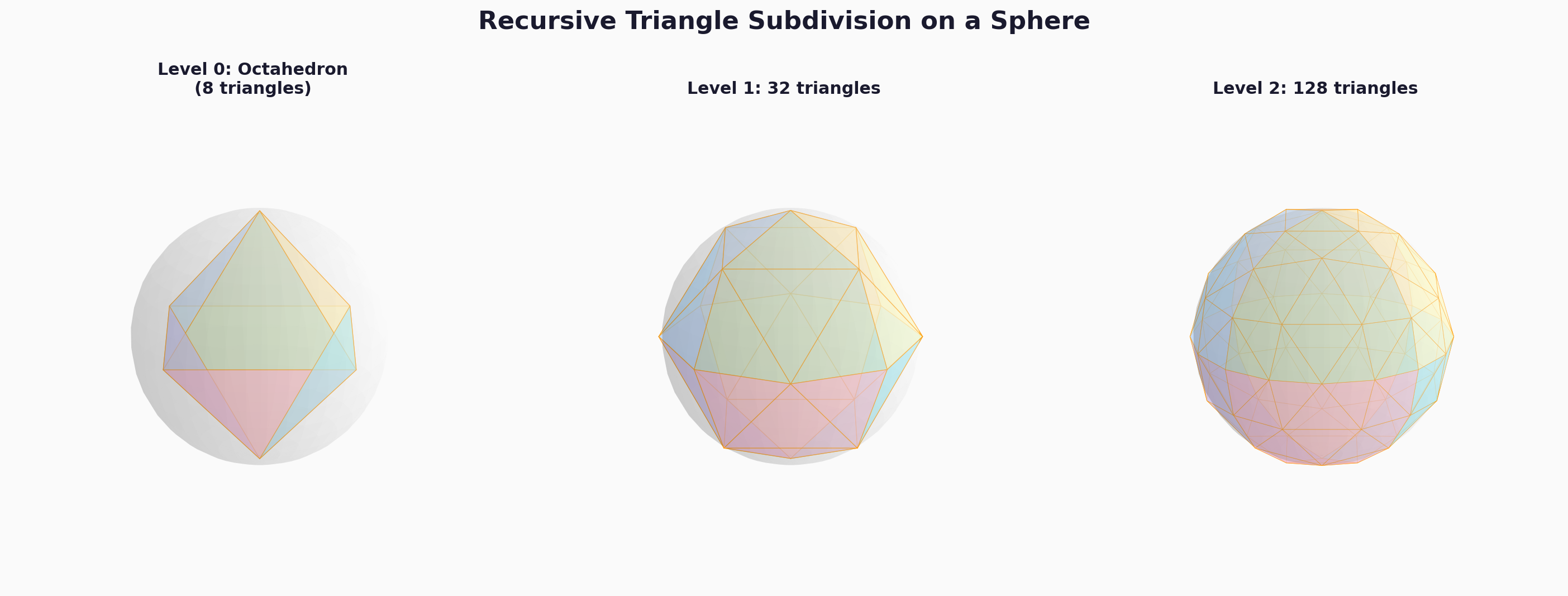

Then I recursively subdivided each triangle by connecting edge midpoints — computed along great circles, not flat-map approximations — splitting each into 4 smaller triangles. Each level doubles the resolution.

Subdividing sphere by triangles

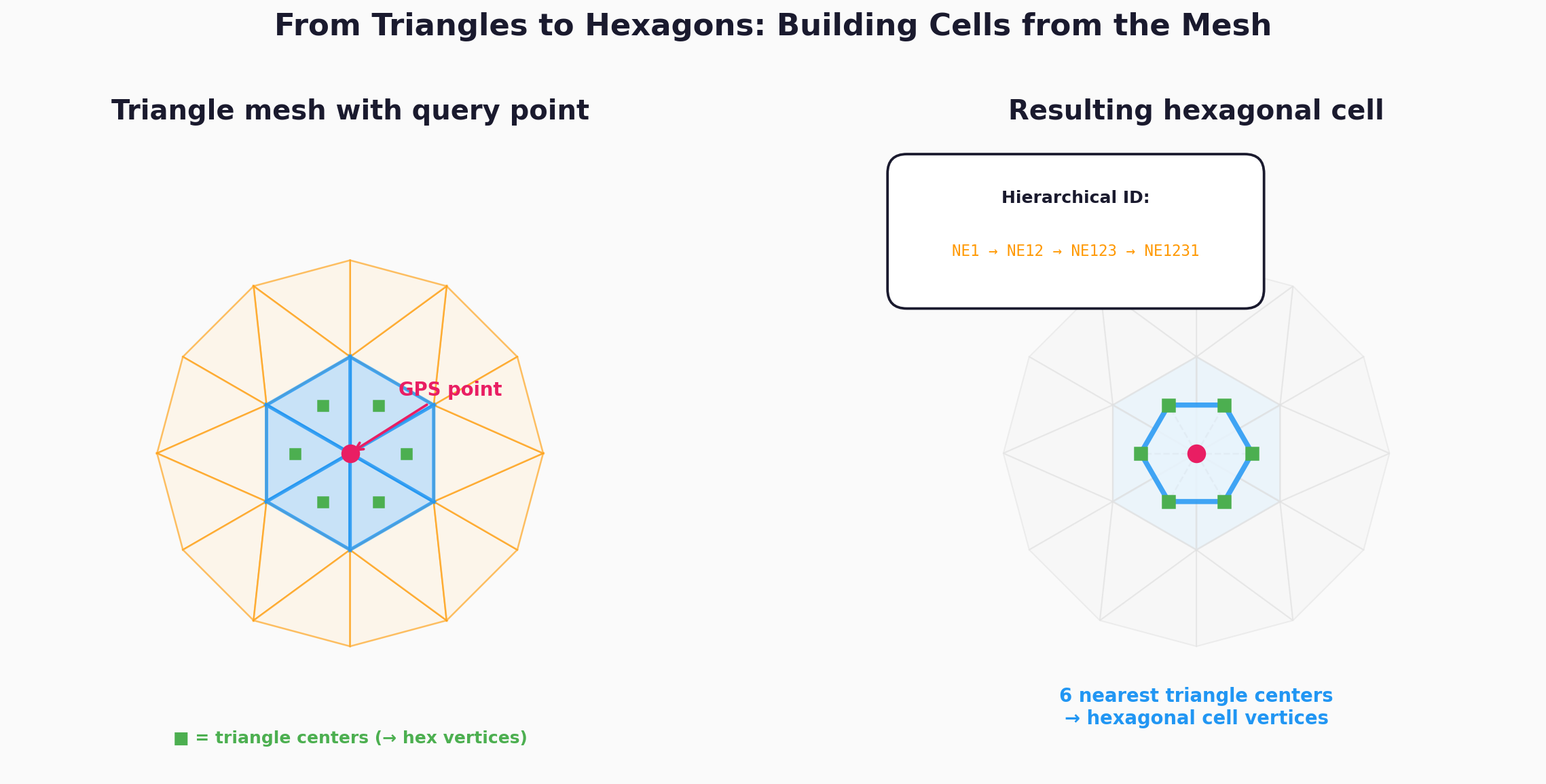

To find the hexagonal zone for any GPS coordinate, I take the 6 triangles closest to that point — their centers form the vertices of a hexagon.

Creating hexagon from triangles

The key properties:

- Hierarchical IDs. Each triangle gets an ID by appending a digit (1–4) at each subdivision level.

NE1231is a child ofNE123, which is a child ofNE12. Coarser resolution is always a prefix of finer resolution — zoom in and out by truncating or extending the string. - Proper spherical math. Midpoints on great circles, centers via Cartesian averaging projected back to the sphere, distances via haversine. No flat-Earth shortcuts.

- Variable resolution. Level 4 gives city-scale zones; level 16 gives block-scale zones.

I remember long evenings after work, sitting with a whiteboard covered in hexagons, triangles, and pentagons, working through the projection geometry. It was deeply satisfying work.

The system wasn’t shipped to production. One thing is to prototype something as a single engineer; another thing is to ship it. Despite this, I was proud of the work — I published the hex grid library on GitHub, got a great review from my diploma reviewer, and was especially pleased that my work had a real application behind it, even if it didn’t make it to prod.

Then I discovered H3

Some time later, Uber open-sourced H3 — a hexagonal hierarchical spatial index. Built for the same domain (ride-hailing), solving the same core problem (spatial discretization), using the same fundamental insight (recursive subdivision of a polyhedron to create hierarchical hexagonal cells on the sphere).

H3 is a more mature and capable system, as you’d expect from years of production engineering. It uses an icosahedron (20 faces) instead of my octahedron (8 faces), giving more uniform cell areas since icosahedral faces are closer to equilateral triangles. It has explicit pentagon handling, compact 64-bit integer indexing, and a rich neighbor/ring API. My implementation has more distortion near the poles and equator, and the “find 6 nearest triangles” approach is a simpler heuristic rather than a full topological mesh.

But the core architecture — subdivide a polyhedron’s spherical faces recursively, use geodesic math, build hexagons from the triangle mesh, leverage hierarchical IDs for multi-resolution analysis — is the same. I arrived at it independently, as an undergraduate.

What I took away

If I were starting this today, I’d just use H3. But I’m glad I didn’t have that option — inventing a solution from scratch taught me far more than using someone else’s ever could.

The fact that the same core ideas emerged independently — from a diploma project and from a world-class engineering team — is, I’ll admit, very satisfying.

The code is still on GitHub if you’re curious.